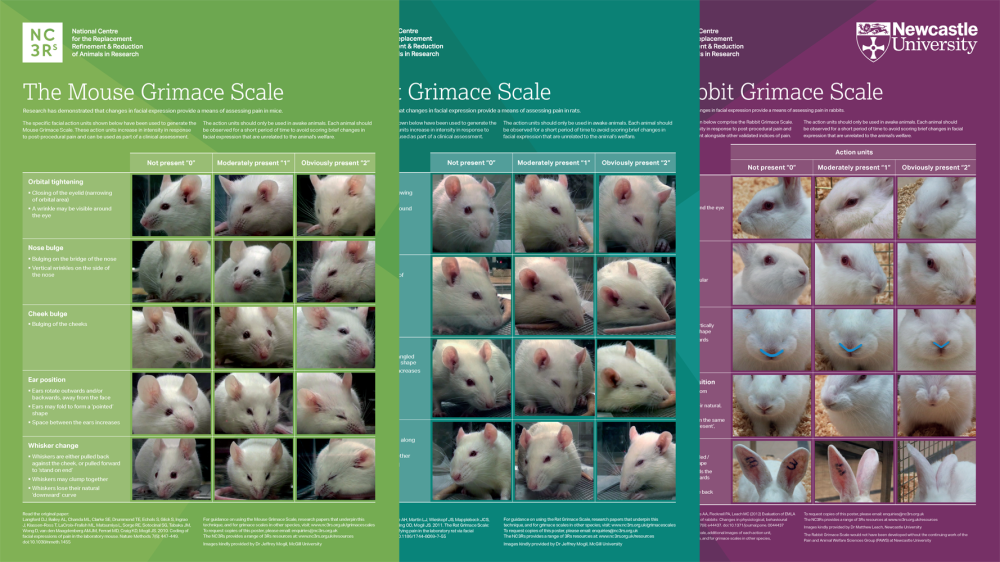

Grimace scale: Mouse

The mouse grimace scale features specific facial action units, increasing in intensity in response to post-procedural pain. These can be used as part of a clinical assessment.

Research has demonstrated that changes in facial expression provide a means of assessing pain in many laboratory species including the mouse, rat and rabbit.

We have produced a poster featuring the mouse grimace scale to help familiarise staff with the specific facial action units, and encourage their implementation as a means of welfare assessment.

Read the original paper

Langford DJ et al. (2010). Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nature Methods 7(6): 447-449. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1455

Available posters

We have copies of The Mouse Grimace Scale poster in a number of languages. Downloadable copies are subject to the T&Cs outlined below.

Download terms and conditions

The proper use of a grimace scale poster requires each of the facial action units to be clear and easily discernible. They therefore must be printed by a professional print service at the full A3 size. Further guidance is included in the cover page which should not be removed from the PDF file.

Any requests to reproduce this poster, or to include it in any publications or training materials, should be directed to enquiries@nc3rs.org.uk. You should include how, why and where the poster will be used so that we can consider your case for approval. It is helpful to include any associated text, so we can see the context in which the poster will be put.

Copyright notice: These posters and their content are owned by the NC3Rs and its partners. The poster should not be adapted, and the content should not be sold or used to generate income.

Papers that validate or use this technique

- Matsumiya LS, Sorge RE, Sotocinal SG et al. (2012). Using the Mouse Grimace Scale to reevaluate the efficacy of postoperative analgesics in laboratory mice. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 51(1): 42-49. PMCID:PMC3276965

- Leach MC et al. (2012). The assessment of post-vasectomy pain in mice using behaviour and the Mouse Grimace Scale. PLOS ONE 7(4): e35656. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035656

- Miller AL and Leach MC (2015). Using the Mouse Grimace Scale to assess pain associated with routine ear notching and the effect of analgesia in laboratory mice. Laboratory Animals 49(2): 117-120. doi:10.1177/0023677214559084

- Miller AL and Leach MC (2015). The Mouse Grimace Scale: A clinically useful tool? PLOS ONE 10(9): e0136000. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136000

- Miller A et al. (2015). The effect of isoflurane anaesthesia and buprenorphine on the mouse grimace scale and behaviour in CBA and DBA/2 mice. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 172: 58-62. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2015.08.038

- Miller AL and Leach MC (2015). The effect of handling method on the mouse grimace scale in two strains of laboratory mice. Laboratory Animals 50(4): 305-7. doi:10.1177/0023677215622144

- Faller KM et al. (2015). Refinement of analgesia following thoracotomy and experimental myocardial infarction using the Mouse Grimace Scale. Experimental Physiology 100(2): 164-172. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2014.083139

- Roughan JV et al. (2015). Meloxicam prevents COX-2-mediated post-surgical inflammation but not pain following laparotomy in mice. European Journal of Pain 20(2): 231-40. doi:10.1002/ejp.712

- Kim JY et al. (2015). Spinal dopaminergic projections control the transition to pathological pain plasticity via a D1/D5-mediated mechanism. Journal of Neuroscience 35(16): 6307-6317. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3481-14.2015

- Bu X et al. (2015). Effects of “danzhi decoction” on chronic pelvic pain, hemodynamics, and proinflammatory factors in the murine model of sequelae of pelvic inflammatory disease. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2015: 547251. doi:10.1155/2015/547251

- Mittal A et al. (2016). Quantification of pain in sickle mice using facial expressions and body measurements. Blood, cells, molecules and diseases 57: 58-66. doi:10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.12.006

- Wu J et al. (2016). Cell cycle inhibition limits development and maintenance of neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Pain 157(2): 488-503. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000393

- Miller AL et al. (2016). Using the mouse grimace scale and behaviour to assess pain in CBA mice following vasectomy. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 181: 160-165. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2016.05.020

- Allweiler SI (2016). How to improve anesthesia and analgesia in small mammals. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice 19(2): 361-377. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2016.01.012

- Duffy SS et al. (2016). Peripheral and central neuroinflammatory changes and pain behaviors in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology 7: 369. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00369

- Hassan AM et al. (2017). Visceral hyperalgesia caused by peptide YY deletion and Y2 receptor antagonism. Scientific Reports 7: 40968. doi:10.1038/srep40968

- Zhu Y et al. (2017). Effect of static magnetic field on pain level and expression of P2X3 receptors in the trigeminal ganglion in mice following experimental tooth movement. Bioelectromagnetics 38(1): 22-30. doi:10.1002/bem.22009

- Hohlbaum K et al. (2017). Severity classification of repeated isoflurane anesthesia in C57BL/6JRj mice: Assessing the degree of distress. PLoS ONE 12(6): e0179588. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0179588

- Wang S et al. (2017). Spontaneous and bite-evoked muscle pain are mediated by a common nociceptive pathway with differential contribution by TRPV1. The Journal of Pain 18(11): 1333-1345. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2017.06.005

- Akintola T et al. (2017). The grimace scale reliably assesses chronic pain in a rodent model of trigeminal neuropathic pain. Neurobiology of Pain 2: 13-17. doi:10.1016/j.ynpai.2017.10.001

- Tuttle AH et al. (2018). A deep neural network to assess spontaneous pain from mouse facial expressions. Molecular Pain 14: 1744806918763658. doi:10.1177/1744806918763658

- Hohlbaum K et al. (2018). Systematic assessment of well-being in mice for procedures using general anesthesia. Journal of Visualized Experiments 20(133). doi:10.3791/57046

- Wang S et al. (2018). Roles of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in spontaneous pain from inflamed masseter muscle. Neuroscience 384: 290-299 doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.05.048

- Dalla Costa E et al. (2018). Can grimace scales estimate the pain status in horses and mice? A statistical approach to identify a classifier. PLOS ONE 13(8): e0200339. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200339

- de Almeida AS et al. (2019). Role of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) on nociception caused by a murine model of breast carcinoma. Pharmacological Research 104576. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104576

- Jirkof P et al. (2019). A safe bet? Inter-laboratory variability in behaviour-based severity assessment. Laboratory Animals 23677219881481. doi:10.1177/0023677219881481

- Ernst L et al. (2019). Semi-automated generation of pictures for the Mouse Grimace Scale: A multi-laboratory analysis (Part 2). Laboratory Animals 23677219881664. doi:10.1177/0023677219881664

- Ernst L et al. (2019). Improvement of the Mouse Grimace Scale set-up for implementing a semi-automated Mouse Grimace Scale scoring (Part 1). Laboratory Animals 23677219881655. doi:10.1177/0023677219881655

- Wang S et al. (2019). TRPV1 and TRPV1-expressing nociceptors mediate orofacial pain behaviors in a mouse model of orthodontic tooth movement. Frontiers of Physiology 10: 1207. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.01207

- Sarfaty AE et al. (2019). Concentration-dependent toxicity after subcutaneous administration of meloxicam to C57BL/6N mice (Mus musculus). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 58(6): 802-809. doi:10.30802/AALAS-JAALAS-19-000037

- Serizawa K et al. (2019). Anti-IL-6 receptor antibody inhibits spontaneous pain at the pre-onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Frontiers of Neurology 10: 341. doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00341

- de Almeida AS et al. (2019). Characterization of cancer-induced nociception in a murine model of breast carcinoma. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 39(5): 605-617. doi:10.1007/s10571-019-00666-8

- Roughan JV and Sevenoaks T (2019). Welfare and scientific considerations of tattooing and ear tagging for mouse identification. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 58(2): 142-153. doi:10.30802/AALAS-JAALAS-18-000057

- Guo W et al. (2019). Voluntary biting behavior as a functional measure of orofacial pain in mice. Physiology and Behavior 204: 129-139. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.02.024

- Herrera C et al. (2019). Analgesic effect of morphine and tramadol in standard toxicity assays in mice injected with venom of the snake Bothrops asper. Toxicon 154: 35-41. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.09.012

- Hohlbaum K et al. (2019). Impact of repeated anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine on the well-being of C57BL/6JRj mice. PLoS One 13(9): e0203559. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0203559

- Mai SHC et al. (2019). Body temperature and mouse scoring systems as surrogate markers of death in cecal ligation and puncture sepsis. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental 6(1): 20. doi:10.1186/s40635-018-0184-3

- Wang S et al. (2019). Roles of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in spontaneous pain from inflamed masseter muscle. Neuroscience 384: 290-299. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.05.048

- Serizawa K et al. (2019). Anti-IL-6 receptor antibody inhibits spontaneous pain at the pre-onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Frontiers in Neurology 10: 341. doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00341

- Guo W et al. (2019). Voluntary biting behaviour as a functional measure of orofacial pain in mice. Physiology and behaviour 204: 129-139. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.02.024

- Cho C et al. (2019). Evaluating analgesic efficacy and administration route following craniotomy in mice using the grimace scale. Scientific Reports 9(1): 359. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-36897-w

- Wang S et al. (2019). TRPV1 and TRPV1-expressing nociceptors mediate orofacial pain behaviours in a mouse model of orthodontic tooth movement. Frontiers in Physiology 10: 1207. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.01207

- Hohlbaum K et al. (2020). Reliability of the mouse grimace scale in c57bl/6jrj mice. Animals 10(9): 1648. doi:10.3390/ani10091648

- Whittaker et al. (2021). Methods used and application of the mouse grimace scale in biomedical research 10 years on: a scoping review. Animals 11(3): 673. doi:10.3390/ani11030673

- Ernst L et al. (2022). A model-specific simplification of the Mouse Grimace Scale based on the pain response of intraperitoneal CCl4 injections. Scientific Reports 12: 10910. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14852-0

Read more about why the grimace scales were developed, and download the scales for use with rats and rabbits.